Jacobson radical

In mathematics, more specifically ring theory, a branch of abstract algebra, the Jacobson radical of a ring R is an ideal which consists of those elements in R which annihilate all simple right R-modules. It happens that substituting "left" in place of "right" in the definition yields the same ideal, and so the notion is left-right symmetric. The Jacobson radical of a ring is frequently denoted by J(R) or rad(R); however to avoid confusion with other radicals of rings, the former notation will be preferred in this article. The Jacobson radical is named after Nathan Jacobson, who was the first to study it for arbitrary rings in (Jacobson 1945).

The Jacobson radical of a ring has numerous internal characterizations, including a few definitions which successfully extend the notion to rings without unity. The radical of a module extends the definition of the Jacobson radical to include modules. The Jacobson radical plays a prominent role in many ring and module theoretic results, such as Nakayama's lemma.

Contents |

Intuitive discussion

As with other radicals of rings, the Jacobson radical can be thought of as a collection of "bad" elements. In this case the "bad" property is that these elements annihilate all simple left and right modules of the ring. For purposes of comparison, consider the nilradical of a commutative ring, which consists of all elements which are nilpotent. In fact for any ring, the nilpotent elements in the center of the ring are also in the Jacobson radical.[1] So, for commutative rings, the nilradical is contained in the Jacobson radical.

The Jacobson radical is very similar to the nilradical in an intuitive sense. A weaker notion of being bad, weaker than being a zero divisor, is being a non-unit (not invertible under multiplication). The Jacobson radical of a ring consists of elements which satisfy a stronger property than being merely a non-unit – in some sense, a member of the Jacobson radical must not "act as a unit" in any module "internal to the ring." More precisely, a member of the Jacobson radical must project under the canonical homomorphism to the zero of every "right division ring" (each non-zero element of which has a right inverse) internal to the ring in question. Concisely, it must belong to every maximal right ideal of the ring. These notions are of course imprecise, but at least explain why the nilradical of a commutative ring is contained in the ring's Jacobson radical.

In yet a simpler way, we may think of the Jacobson radical of a ring as method to "mod out bad elements" of the ring – that is, members of the Jacobson radical act as 0 in the quotient ring, R/J(R). If N is the nilradical of commutative ring R, then the quotient ring R/N has no nilpotent elements. Similarly for any ring R, the quotient ring has J(R/J(R))={0} and so all of the "bad" elements in the Jacobson radical have been removed by modding out J(R). Elements of the Jacobson radical and nilradical can be therefore seen as generalizations of 0.

Equivalent characterizations

The Jacobson radical of a ring has various internal and external characterizations. The following equivalences appear in many noncommutative algebra texts such as (Anderson 1992, §15), (Isaacs 1993, §13B), and (Lam 2001, Ch 2).

The following are equivalent characterizations of the Jacobson radical in rings with unity (characterizations for rings without unity are given immediately afterward):

- J(R) equals the intersection of all maximal right ideals of the ring. It is also true that J(R) equals the intersection of all maximal left ideals within the ring.[2] These characterizations are internal to the ring, since one only needs to find the maximal right ideals of the ring. For example, if a ring is local, and has a unique maximal right ideal, then this unique maximal right ideal is an ideal because it is exactly J(R). Maximal ideals are in a sense easier to look for than annihilators of modules. This characterization is deficient, however, because it does not prove useful when working computationally with J(R). The left-right symmetry of these two definitions is remarkable and has various interesting consequences.[3][4] This symmetry stands in contrast to the lack of symmetry in the socles of R, for it may happen that soc(RR) is not equal to soc(RR). However, J(R) is not necessarily equal to the intersection of all maximal (double-sided) ideals within R. For instance, if V is a countable direct sum of copies of a field k and R=End(V) (the ring of endomorphisms of V as a k-module), then J(R)=0 because R is known to be von Neumann regular, but there is exactly one maximal double-sided ideal in R consisting of endomorphisms with finite-dimensional image. (Lam 2001, Ex. 3.15)

- J(R) equals the sum of all superfluous right ideals (or symmetrically, the sum of all superfluous left ideals) of R. Comparing this with the previous definition, the sum of superfluous right ideals equals the intersection of maximal right ideals. This phenomenon is reflected dually for the right socle of R: soc(RR) is both the sum of minimal right ideals and the intersection of essential right ideals. In fact, these two astounding relationships hold for the radicals and socles of modules in general.

- As defined in the introduction, J(R) equals the intersection of all annihilators of simple right R-modules, however it is also true that it is the intersection of annihilators of simple left modules. An ideal that is the annihilator of a simple module is known as a primitive ideal, and so a reformulation of this states that the Jacobson radical is the intersection of all primitive ideals. Although this characterization is not useful computationally, or as useful as the previous two characterizations in aiding intuition, it is useful in studying modules over rings. For instance, if U is right R-module, and V is a maximal submodule of U, U·J(R) is contained in V, where U·J(R) denotes all products of elements of J(R) (the "scalars") with elements in U, on the right. This follows from the fact that the quotient module, U/V is simple and hence annihilated by J(R). As another example, this result motivates Nakayama's lemma.

- J(R) is the unique right ideal of R maximal with the property that every element is right quasiregular.[5][6] Alternatively, one could replace "right" with "left" in the previous sentence.[7] This characterization of the Jacobson radical is useful both computationally and in aiding intuition. Furthermore, this characterization is useful in studying modules over a ring. Nakayama's lemma is perhaps the most well-known instance of this. Although every element of the J(R) is necessarily quasiregular, not every quasiregular element is necessarily a member of J(R).[8]

- While not every quasiregular element is in J(R), it can be shown that y is in J(R) if and only if xy is left quasiregular for all x in R. (Lam 2001, p. 50)

For rings without unity it is possible for R=J(R), however the equation that J(R/J(R))={0} still holds. The following are equivalent characterizations of J(R) for rings without unity appear in (Lam 2001, p. 63):

- The notion of left quasiregularity can be generalized in the following way. Call an element a in R left generalized quasiregular if there exists c in R such that c+a-ca= 0. Then J(R) consists of every element a for which ra is left generalized quasiregular for all r in R. It can be checked that this definition coincides with the previous quasiregular definition for rings with unity.

- For a ring without unity, the definition of a left simple module M is amended by adding the condition that R•M ≠ 0. With this understanding, J(R) may be defined as the intersection of all simple left R modules, or just R if there are no simple left R modules. Rings without unity with no simple modules do exist, in which case R=J(R), and the ring is called a radical ring. By using the generalized quasiregular characterization of the radical, it is clear that if one finds a ring with J(R) nonzero, then J(R) is a radical ring when considered as a ring without unity.

Examples

- Rings for which J(R) is {0} are called semiprimitive rings, or sometimes "Jacobson semisimple rings". The Jacobson radical of any field, any von Neumann regular ring and any left or right primitive ring is {0}. The Jacobson radical of the integers is {0}.

- The Jacobson radical of the ring Z/12Z (see modular arithmetic) is 6Z/12Z, which is the intersection of the maximal ideals 2Z/12Z and 3Z/12Z.

- If K is a field and R is the ring of all upper triangular n-by-n matrices with entries in K, then J(R) consists of all upper triangular matrices with zeros on the main diagonal.

- If K is a field and R = K[[X1, ..., Xn]] is a ring of formal power series, then J(R) consists of those power series whose constant term is zero. More generally: the Jacobson radical of every local ring is the unique maximal ideal of the ring, which consists precisely of the ring's non-units.

- Start with a finite, acyclic quiver Γ and a field K and consider the quiver algebra KΓ (as described in the quiver article). The Jacobson radical of this ring is generated by all the paths in Γ of length ≥ 1.

- The Jacobson radical of a C*-algebra is {0}. This follows from the Gelfand–Naimark theorem and the fact for a C*-algebra, a topologically irreducible *-representation on a Hilbert space is algebraically irreducible, so that its kernel is a primitive ideal in the purely algebraic sense (see spectrum of a C*-algebra).

Properties

- If R is unital and is not the trivial ring {0}, the Jacobson radical is always distinct from R since rings with unity always have maximal right ideals. However, some important theorems and conjectures in ring theory consider the case when J(R) = R - "If R is a nil ring (that is, each of its elements is nilpotent), is the polynomial ring R[x] equal to its Jacobson radical?" is equivalent to the open Köthe conjecture. (Smoktunowicz 2006, §5)

- The Jacobson radical of the ring R/J(R) is zero. Rings with zero Jacobson radical are called semiprimitive rings.

- A ring is semisimple if and only if it is Artinian and its Jacobson radical is zero.

- If f : R → S is a surjective ring homomorphism, then f(J(R)) ⊆ J(S).

- If M is a finitely generated left R-module with J(R)M = M, then M = 0 (Nakayama's lemma).

- J(R) contains all central nilpotent elements, but contains no idempotent elements except for 0.

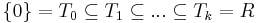

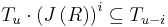

- J(R) contains every nil ideal of R. If R is left or right Artinian, then J(R) is a nilpotent ideal. This can actually be made stronger: If

is a composition series for the right R-module R (such a series is sure to exist if R is right artinian, and there is a similar left composition series if R is left artinian), then

is a composition series for the right R-module R (such a series is sure to exist if R is right artinian, and there is a similar left composition series if R is left artinian), then  . (Proof: Since the factors

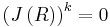

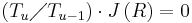

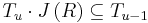

. (Proof: Since the factors  are simple right R-modules, right multiplication by any element of J(R) annihilates these factors. In other words,

are simple right R-modules, right multiplication by any element of J(R) annihilates these factors. In other words,  , whence

, whence  . Consequently, induction over i shows that all nonnegative integers i and u (for which the following makes sense) satisfy

. Consequently, induction over i shows that all nonnegative integers i and u (for which the following makes sense) satisfy  . Applying this to u = i = k yields the result.) Note, however, that in general the Jacobson radical need not consist of only the nilpotent elements of the ring.

. Applying this to u = i = k yields the result.) Note, however, that in general the Jacobson radical need not consist of only the nilpotent elements of the ring.

- If R is commutative and finitely generated as a Z-module, then J(R) is equal to the nilradical of R.

- In a right Noetherian ring, J(R) is a superfluous right ideal.

Notes

References

- Anderson, Frank W.; Fuller, Kent R. (1992), Rings and categories of modules, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 13 (2 ed.), New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. x+376, ISBN 0-387-97845-3, MR(94i:16001) 1245487 (94i:16001)

- Atiyah, M. F.; Macdonald, I. G. (1969), Introduction to commutative algebra, Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Reading, Mass.-London-Don Mills, Ont., pp. ix+128, MR(39 #4129) 0242802 (39 #4129)

- N. Bourbaki. Éléments de Mathématique.

- Herstein, I. N. (1994), Noncommutative rings, Carus Mathematical Monographs, 15, Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America, pp. xii+202, ISBN 0-88385-015-X, MR(97m:16001) 1449137 (97m:16001)

- Isaacs, I. M. (1993). Algebra, a graduate course (1st edition ed.). Brooks/Cole Publishing Company. ISBN 0-534-19002-2.

- Jacobson, Nathan (1945), "The radical and semi-simplicity for arbitrary rings", American Journal of Mathematics 67: 300–320, doi:10.2307/2371731, ISSN 0002-9327, MR12271

- Lam, T. Y. (2001), A first course in noncommutative rings, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 131 (2 ed.), New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. xx+385, ISBN 0-387-95183-0, MR(2002c:16001) 1838439 (2002c:16001)

- Pierce, Richard S. (1982), Associative algebras, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 88, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. xii+436, ISBN 0-387-90693-2, MR(84c:16001) 674652 (84c:16001)